Hepatitis C is an infectious disease affecting primarily the liver, caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV). The infection is often asymptomatic, but chronic infection can lead to scarring of the liver and ultimately to cirrhosis, which is generally apparent after many years. In some cases, those with cirrhosis will go on to develop liver failure, liver cancer, or life-threatening esophageal and gastric varices.

Hep

C is a viral infection that causes inflammation and scarring of the

liver. The prognosis of someone with this disease varies greatly. Some

people are able to get rid of the disease entirely, some are able to

live symptom free for decades and others have many more complications

early on. The difference in quality of life can greatly depend on the

overall health of the person. Holistic health can support the health of

people and the health of their liver for increased quality of life.

- See more at: http://www.herbalremediesadvice.org/hepatitis-c.html#sthash.vwh03V0B.dpuf

Hep

C is a viral infection that causes inflammation and scarring of the

liver. The prognosis of someone with this disease varies greatly. Some

people are able to get rid of the disease entirely, some are able to

live symptom free for decades and others have many more complications

early on. The difference in quality of life can greatly depend on the

overall health of the person. Holistic health can support the health of

people and the health of their liver for increased quality of life.

- See more at: http://www.herbalremediesadvice.org/hepatitis-c.html#sthash.vwh03V0B.dpuf

Hep

C is a viral infection that causes inflammation and scarring of the

liver. The prognosis of someone with this disease varies greatly. Some

people are able to get rid of the disease entirely, some are able to

live symptom free for decades and others have many more complications

early on. The difference in quality of life can greatly depend on the

overall health of the person. Holistic health can support the health of

people and the health of their liver for increased quality of life.

- See more at: http://www.herbalremediesadvice.org/hepatitis-c.html#sthash.vwh03V0B.dpuf

is an infectious disease affecting primarily the liver, caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV). The infection is often asymptomatic, but chronic infection can lead to scarring of the liver and ultimately to cirrhosis, which is generally apparent after many years. In some cases, those with cirrhosis will go on to develop liver failure, liver cancer, or life-threatening esophageal and gastric varices.

HCV is spread primarily by blood-to-blood contact associated with intravenous drug use, poorly sterilized medical equipment, and transfusions. An estimated 150–200 million people worldwide are infected with hepatitis C. The existence of hepatitis C (originally identifiable only as a type of non-A non-B hepatitis) was suggested in the 1970s and proven in 1989. Hepatitis C infects only humans and chimpanzees.

The virus persists in the liver in about 85% of those infected. This

chronic infection can be treated with medication: the standard therapy

is a combination of peginterferon and ribavirin, with either boceprevir or telaprevir added in some cases. Overall, 50–80% of people treated are cured. Those who develop cirrhosis or liver cancer may require a liver transplant. Hepatitis C is the leading reason for liver transplantation, though the virus usually recurs after transplantation. No vaccine against hepatitis C is available.

History

In the mid-1970s, Harvey J. Alter, Chief of the Infectious Disease Section in the Department of Transfusion Medicine at the National Institutes of Health, and his research team demonstrated how most post-transfusion hepatitis cases were not due to hepatitis A or B viruses. Despite this discovery, international research efforts to identify the virus, initially called non-A, non-B hepatitis (NANBH), failed for the next decade. In 1987, Michael Houghton, Qui-Lim Choo, and George Kuo at Chiron Corporation, collaborating with Dr. D.W. Bradley at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, used a novel molecular cloning approach to identify the unknown organism and develop a diagnostic test.

In 1988, Alter confirmed the virus by verifying its presence in a panel

of NANBH specimens. In April 1989, the discovery of HCV was published

in two articles in the journal Science. The discovery led to significant improvements in diagnosis and improved antiviral treatment. In 2000, Drs. Alter and Houghton were honored with the Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research

for "pioneering work leading to the discovery of the virus that causes

hepatitis C and the development of screening methods that reduced the

risk of blood transfusion-associated hepatitis in the U.S. from 30% in

1970 to virtually zero in 2000."

Chiron filed for several patents on the virus and its diagnosis.

A competing patent application by the CDC was dropped in 1990 after

Chiron paid $1.9 million to the CDC and $337,500 to Bradley. In 1994,

Bradley sued Chiron, seeking to invalidate the patent, have himself

included as a coinventor, and receive damages and royalty income. He

dropped the suit in 1998 after losing before an appeals court.

It is estimated that 150–200 million people, or ~3% of the world's population, are living with chronic hepatitis C.About 3–4 million people are infected per year, and more than 350,000 people die yearly from hepatitis C-related diseases.

During 2010 it is estimated that 16,000 people died from acute

infections while 196,000 deaths occurred from liver cancer secondary to

the infection.

Rates have increased substantially in the 20th century due to a

combination of intravenous drug abuse and reused but poorly sterilized

medical equipment.

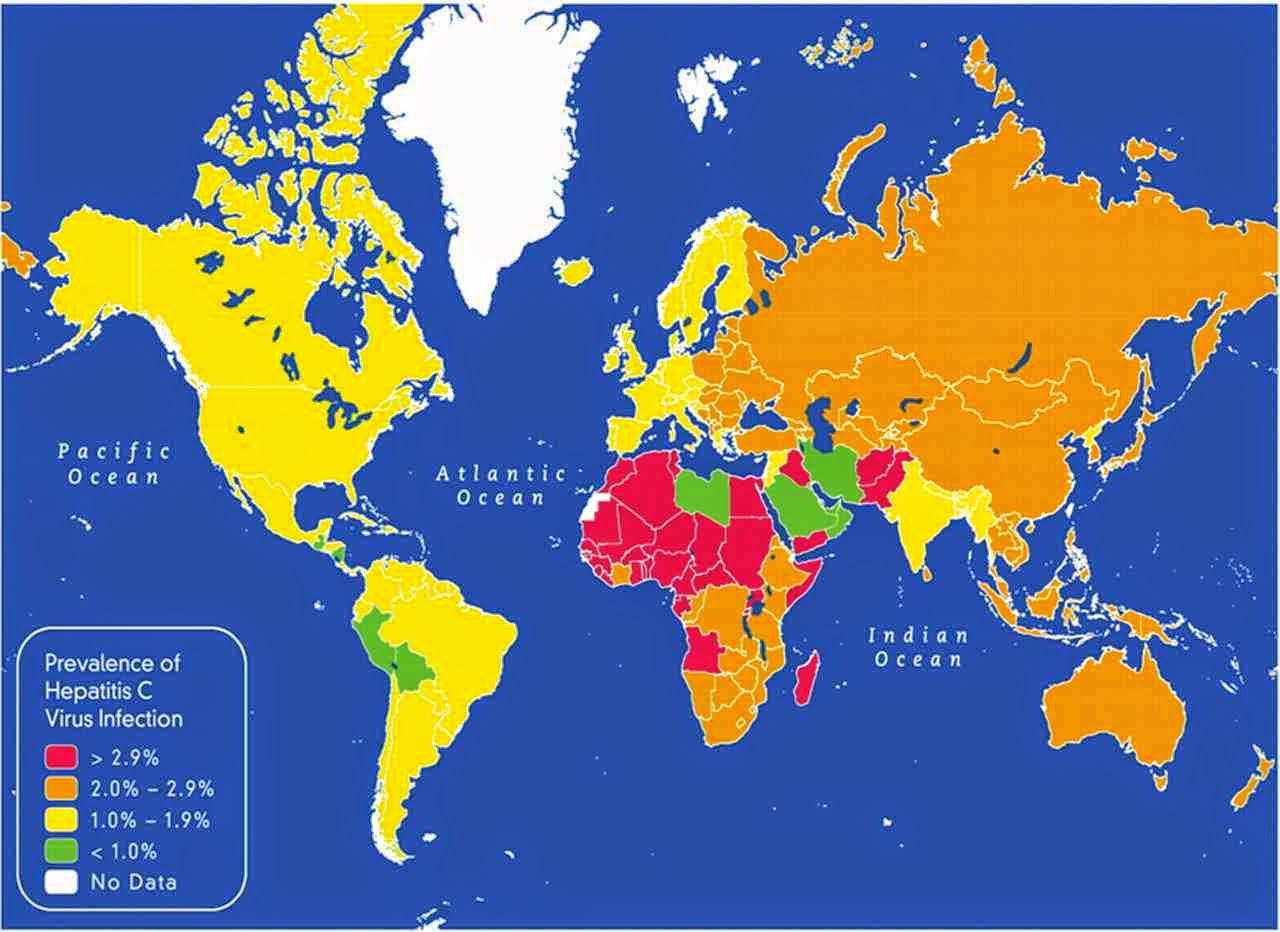

Rates are high (>3.5% population infected) in Central and East

Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, they are intermediate

(1.5%-3.5%) in South and Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Andean,

Central and Southern Latin America, Caribbean, Oceania, Australasia and

Central, Eastern and Western Europe; and they are low (<1.5%) in Asia

Pacific, Tropical Latin America and North America.

Among those chronically infected, the risk of cirrhosis

after 20 years varies between studies but has been estimated at ~10–15%

for men and ~1–5% for women. The reason for this difference is not

known. Once cirrhosis is established, the rate of developing hepatocellular carcinoma is ~1–4% per year.

Rates of new infections have decreased in the Western world since the

1990s due to improved screening of blood before transfusion.

In the United States, about 2% of people have hepatitis C, with the number of new cases per year stabilized at 17,000 since 2007. The number of deaths from hepatitis C has increased to 15,800 in 2008 and by 2007 had overtaken HIV/AIDS as a cause of death in the USA. This mortality rate is expected to increase, as those infected by transfusion before HCV testing become apparent. In Europe the percentage of people with chronic infections has been estimated to be between 0.13 and 3.26%.

The total number of people with this infection is higher in some countries in Africa and Asia. Countries with particularly high rates of infection include Egypt (22%), Pakistan (4.8%) and China (3.2%). It is believed that the high prevalence in Egypt is linked to a now-discontinued mass-treatment campaign for schistosomiasis, using improperly sterilized glass syringes.

Rates are high (>3.5% population infected) in Central and East

Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, they are intermediate

(1.5%-3.5%) in South and Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Andean,

Central and Southern Latin America, Caribbean, Oceania, Australasia and

Central, Eastern and Western Europe; and they are low (<1.5%) in Asia

Pacific, Tropical Latin America and North America.

Among those chronically infected, the risk of cirrhosis

after 20 years varies between studies but has been estimated at ~10–15%

for men and ~1–5% for women. The reason for this difference is not

known. Once cirrhosis is established, the rate of developing hepatocellular carcinoma is ~1–4% per year.

Rates of new infections have decreased in the Western world since the

1990s due to improved screening of blood before transfusion.

In the United States, about 2% of people have hepatitis C, with the number of new cases per year stabilized at 17,000 since 2007. The number of deaths from hepatitis C has increased to 15,800 in 2008 and by 2007 had overtaken HIV/AIDS as a cause of death in the USA. This mortality rate is expected to increase, as those infected by transfusion before HCV testing become apparent. In Europe the percentage of people with chronic infections has been estimated to be between 0.13 and 3.26%.

The total number of people with this infection is higher in some countries in Africa and Asia. Countries with particularly high rates of infection include Egypt (22%), Pakistan (4.8%) and China (3.2%). It is believed that the high prevalence in Egypt is linked to a now-discontinued mass-treatment campaign for schistosomiasis, using improperly sterilized glass syringes.

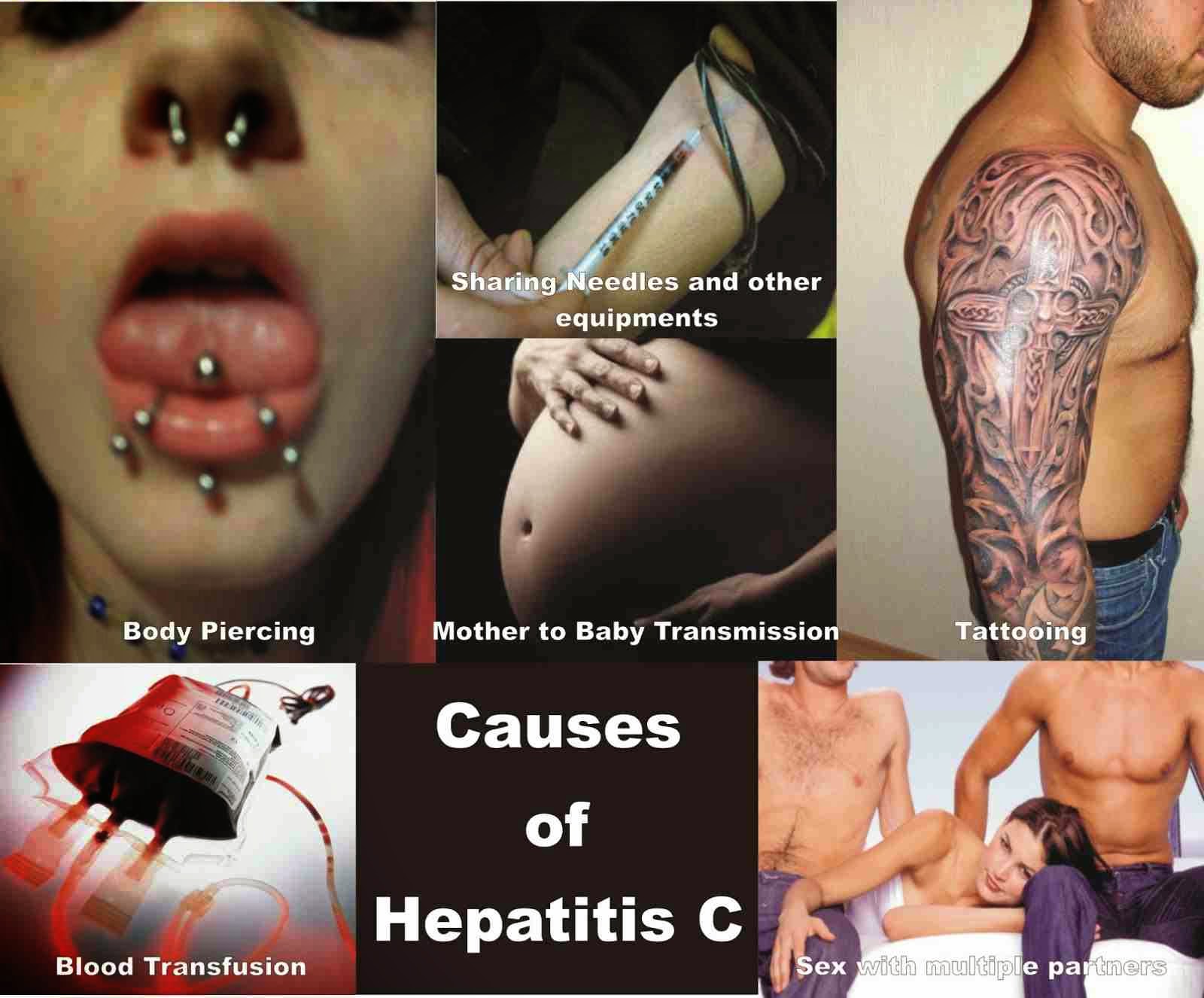

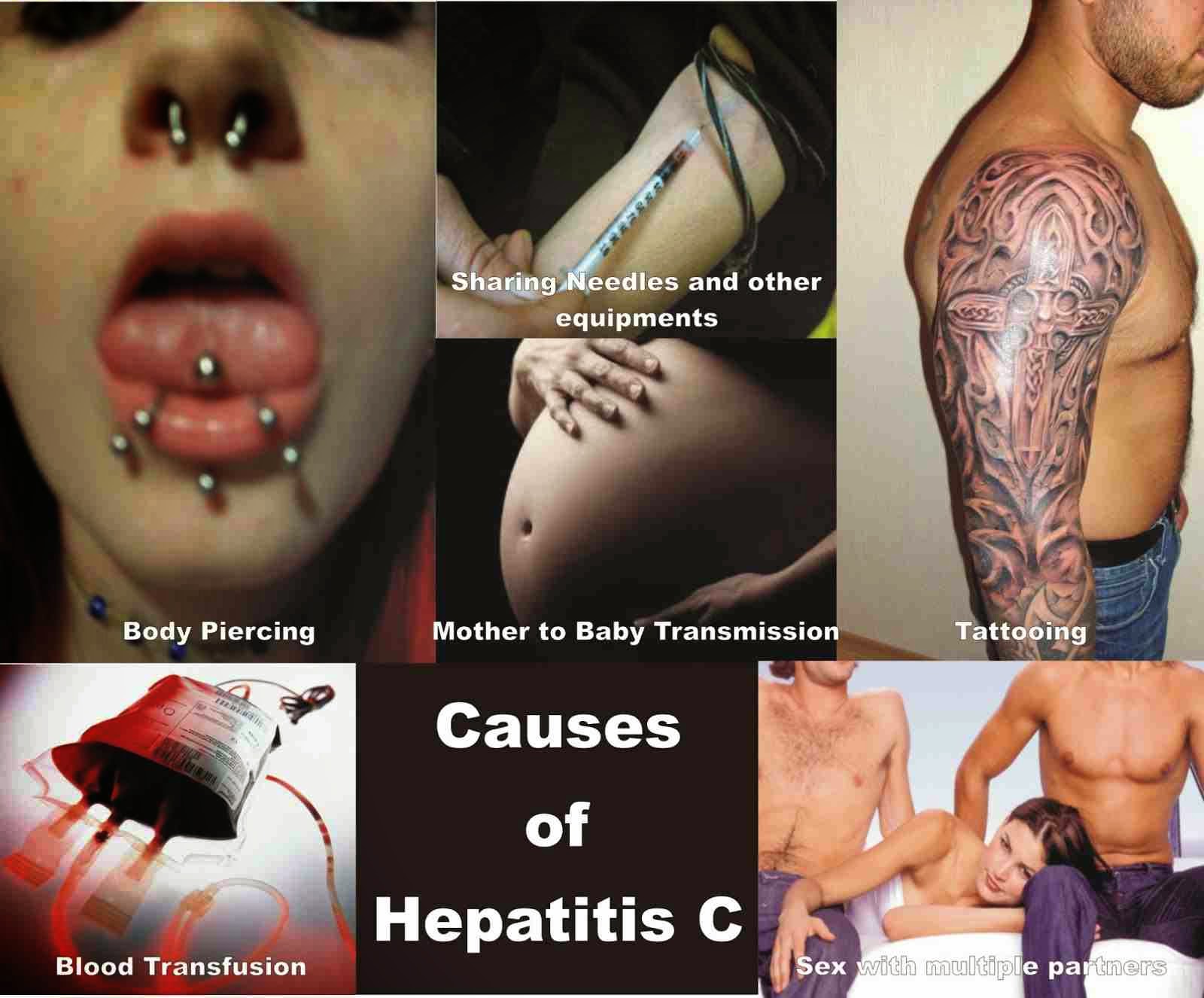

Transmission / Exposure

Hepatitis C is usually spread when blood from a person infected with the Hepatitis

C virus enters the body of someone who is not infected. Today, most people

become infected with the Hepatitis C virus by sharing needles or other equipment

to inject drugs. Before 1992, when widespread screening of the blood supply

began in the United States, Hepatitis C was also commonly spread through

blood transfusions and organ transplants.

People can become infected with the Hepatitis

C virus during such activities as

- Sharing needles, syringes, or other equipment to inject drugs

- Needlestick injuries in health care settings

- Being born to a mother who has Hepatitis C

Less commonly, a person can also get Hepatitis

C virus infection through

- Sharing personal care items that may have come in contact with another

person’s blood, such as razors or toothbrushes

- Having sexual contact with a person infected with the Hepatitis

C virus

-

-

HCV in children and pregnancy

Compared with adults, infection in children is much less well

understood. Worldwide the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in

pregnant women and children has been estimated to 1–8% and 0.05–5%

respectively.

The vertical transmission rate has been estimated to be 3–5% and there

is a high rate of spontaneous clearance (25–50%) in the children. Higher

rates have been reported for both vertical transmission (18%, 6–36% and

41%). and prevalence in children (15%).

In developed countries transmission around the time of birth is now

the leading cause of HCV infection. In the absence of virus in the

mother's blood transmission seems to be rare.

Factors associated with an increased rate of infection include membrane

rupture of longer than 6 hours before delivery and procedures exposing

the infant to maternal blood.

Cesarean sections are not recommended. Breast feeding is considered

safe if the nipples are not damaged. Infection around the time of birth

in one child does not increase the risk in a subsequent pregnancy. All

genotypes appear to have the same risk of transmission.

HCV infection is frequently found in children who have previously

been presumed to have non-A, non-B hepatitis and cryptogenic liver

disease. The presentation in childhood may be asymptomatic or with elevated liver function tests. While infection is commonly asymptomatic both cirrhosis with liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma may occur in childhood.

Can Hepatitis C be spread through sexual contact?

Yes, but the risk of transmission from sexual contact is believed to

be low. The risk increases for those who have multiple sex partners, have

a sexually transmitted disease, engage in rough sex, or are infected with

HIV. More research is needed to better understand how and when Hepatitis

C can be spread through sexual contact.

Can you get Hepatitis C by getting a tattoo or

piercing?

A few major research studies have not shown Hepatitis C to be spread

through licensed, commercial tattooing facilities. However, transmission

of Hepatitis C (and other infectious diseases) is possible when poor infection-control

practices are used during tattooing or piercing. Body art is becoming increasingly

popular in the United States, and unregulated tattooing and piercing are

known to occur in prisons and other informal or unregulated settings. Further

research is needed to determine if these types of settings and exposures

are responsible for Hepatitis C virus transmission.

Can Hepatitis C be spread within a household?

Yes, but this does not occur very often. If Hepatitis C virus is spread

within a household, it is most likely a result of direct, through-the-skin

exposure to the blood of an infected household member.

How should blood spills be cleaned from surfaces to make sure that Hepatitis C virus is gone?

Any blood spills — including dried blood, which can still be

infectious — should be cleaned using a dilution of one part household

bleach to 10 parts water. Gloves should be worn when cleaning up blood

spills.

How long does the Hepatitis C virus survive outside the body?

The Hepatitis C virus can survive outside the body at room

temperature, on environmental surfaces, for at least 16 hours but no

longer than 4 days.

What are ways Hepatitis C is not spread?

Hepatitis C virus is not spread by sharing eating utensils, breastfeeding,

hugging, kissing, holding hands, coughing, or sneezing. It is also not spread

through food or water.

Who is at risk for Hepatitis C?

Some people are at increased risk for Hepatitis

C, including

- Current injection drug users (currently the most common way Hepatitis

C virus is spread in the United States)

- Past injection drug users, including those who injected only one

time or many years ago

- Recipients of donated blood, blood products, and organs (once a

common means of transmission but now rare in the United States since

blood screening became available in 1992)

- People who received a blood product for clotting problems made before

1987

- Hemodialysis patients or persons who spent many years on dialysis

for kidney failure

- People who received body piercing or tattoos done with non-sterile

instruments

- People with known exposures to the Hepatitis C virus, such as

- Health care workers injured by needlesticks

- Recipients of blood or organs from a donor who tested positive

for the Hepatitis C virus

- HIV-infected persons

- Children born to mothers infected with the Hepatitis C virus

Less common risks include:

Less common risks include:

- Having sexual contact with a person who is infected with the Hepatitis

C virus

- Sharing personal care items, such as razors or toothbrushes, that

may have come in contact with the blood of an infected person

_-_en.svg.png)

What is the risk of a pregnant woman passing Hepatitis

C to her baby?

Hepatitis C is rarely passed from a pregnant woman to her baby. About

4 of every 100 infants born to mothers with Hepatitis C become infected

with the virus. However, the risk becomes greater if the mother has both

HIV infection and Hepatitis C.

Can a person get Hepatitis C from a mosquito or

other insect bite?

Hepatitis C virus has not been shown to be transmitted by mosquitoes

or other insects.

Can I donate blood, organs, or semen if I have

Hepatitis C?

No, if you ever tested positive for the Hepatitis C virus (or Hepatitis

B virus), experts recommend never donating blood, organs, or semen because

this can spread the infection to the recipient.

Signs and symptoms

acute symptoms

Hepatitis C infection causes acute symptoms in 15% of cases. Symptoms are generally mild and vague, including a decreased appetite, fatigue, nausea, muscle or joint pains, and weight loss and rarely does acute liver failure result. Most cases of acute infection are not associated with jaundice. The infection resolves spontaneously in 10–50% of cases, which occurs more frequently in individuals who are young and female.

Chronic symptoms

About 80% of those exposed to the virus develop a chronic infection.

This is defined as the presence of detectable viral replication for at

least six months. Most experience minimal or no symptoms during the

initial few decades of the infection. Chronic hepatitis C can be associated with fatigue and mild cognitive problems. Chronic infection after several years may cause cirrhosis or liver cancer. The liver enzymes are normal in 7–53%. Late relapses after apparent cure have been reported, but these can be difficult to distinguish from reinfection.

Fatty changes to the liver occur in about half of those infected and are usually present before cirrhosis develops. Usually (80% of the time) this change affects less than a third of the liver. Worldwide hepatitis C is the cause of 27% of cirrhosis cases and 25% of hepatocellular carcinoma. About 10–30% of those infected develop cirrhosis over 30 years. Cirrhosis is more common in those also infected with hepatitis B, schistosoma, or HIV, in alcoholics and in those of male gender. In those with hepatitis C, excess alcohol increases the risk of developing cirrhosis 100-fold. Those who develop cirrhosis have a 20-fold greater risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. This transformation occurs at a rate of 1–3% per year. Being infected with hepatitis B in additional to hepatitis C increases this risk further.

Liver cirrhosis may lead to portal hypertension, ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdomen), easy bruising or bleeding, varices (enlarged veins, especially in the stomach and esophagus), jaundice, and a syndrome of cognitive impairment known as hepatic encephalopathy. Ascites occurs at some stage in more than half of those who have a chronic infection.

Fatty changes to the liver occur in about half of those infected and are usually present before cirrhosis develops. Usually (80% of the time) this change affects less than a third of the liver. Worldwide hepatitis C is the cause of 27% of cirrhosis cases and 25% of hepatocellular carcinoma. About 10–30% of those infected develop cirrhosis over 30 years. Cirrhosis is more common in those also infected with hepatitis B, schistosoma, or HIV, in alcoholics and in those of male gender. In those with hepatitis C, excess alcohol increases the risk of developing cirrhosis 100-fold. Those who develop cirrhosis have a 20-fold greater risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. This transformation occurs at a rate of 1–3% per year. Being infected with hepatitis B in additional to hepatitis C increases this risk further.

Liver cirrhosis may lead to portal hypertension, ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdomen), easy bruising or bleeding, varices (enlarged veins, especially in the stomach and esophagus), jaundice, and a syndrome of cognitive impairment known as hepatic encephalopathy. Ascites occurs at some stage in more than half of those who have a chronic infection.

The most common problem due to hepatitis C but not involving the liver is mixed cryoglobulinemia (usually the type II form) — an inflammation of small and medium-sized blood vessels. Hepatitis C is also associated with Sjögren's syndrome (an autoimmune disorder); thrombocytopenia; lichen planus; porphyria cutanea tarda; necrolytic acral erythema; insulin resistance; diabetes mellitus; diabetic nephropathy; autoimmune thyroiditis and B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Thrombocytopenia is estimated to occur in 0.16% to 45.4% of people with chronic hepatitis C. 20–30% of people infected have rheumatoid factor — a type of antibody. Possible associations include Hyde's prurigo nodularis and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Cardiomyopathy with associated arrhythmias has also been reported. A variety of central nervous system disorders have been reported. Chronic infection seems to be associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer.

Persons who have been infected with hepatitis C may appear to clear the virus but remain infected. The virus is not detectable with conventional testing but can be found with ultra-sensitive tests. The original method of detection was by demonstrating the viral genome

within liver biopsies, but newer methods include an antibody test for

the virus' core protein and the detection of the viral genome after

first concentrating the viral particles by ultracentrifugation.

A form of infection with persistently moderately elevated serum liver

enzymes but without antibodies to hepatitis C has also been reported.This form is known as cryptogenic occult infection.

Several clinical pictures have been associated with this type of infection.

It may be found in people with anti-hepatitis-C antibodies but with

normal serum levels of liver enzymes; in antibody-negative people with

ongoing elevated liver enzymes of unknown cause; in healthy populations

without evidence of liver disease; and in groups at risk for HCV

infection including those on haemodialysis or family members of people

with occult HCV. The clinical relevance of this form of infection is

under investigation.

The consequences of occult infection appear to be less severe than with

chronic infection but can vary from minimal to hepatocellular

carcinoma.

Several clinical pictures have been associated with this type of infection.

It may be found in people with anti-hepatitis-C antibodies but with

normal serum levels of liver enzymes; in antibody-negative people with

ongoing elevated liver enzymes of unknown cause; in healthy populations

without evidence of liver disease; and in groups at risk for HCV

infection including those on haemodialysis or family members of people

with occult HCV. The clinical relevance of this form of infection is

under investigation.

The consequences of occult infection appear to be less severe than with

chronic infection but can vary from minimal to hepatocellular

carcinoma.

The rate of occult infection in those apparently cured is controversial but appears to be low.40% of those with hepatitis but with both negative hepatitis C serology

and the absence of detectable viral genome in the serum have hepatitis C

virus in the liver on biopsy. How commonly this occurs in children is unknown.

The rate of occult infection in those apparently cured is controversial but appears to be low.40% of those with hepatitis but with both negative hepatitis C serology

and the absence of detectable viral genome in the serum have hepatitis C

virus in the liver on biopsy. How commonly this occurs in children is unknown.

What are the symptoms of acute Hepatitis C?

Approximately 70%–80% of people with acute Hepatitis

C do not have any symptoms. Some people, however, can have mild to severe

symptoms soon after being infected, including

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Dark urine

- Clay-colored bowel movements

- Joint pain

- Jaundice (yellow color in the skin or eyes)

How soon after exposure to Hepatitis C do symptoms

appear?

If symptoms occur, the average time is 6–7 weeks after exposure, but

this can range from 2 weeks to 6 months. However, many people infected with

the Hepatitis C virus do not develop symptoms.

Can a person spread Hepatitis C without having

symptoms?

Yes, even if a person with Hepatitis C has no symptoms, he or she can

still spread the virus to others.

Is it possible to have Hepatitis C and not know

it?

Yes, many people who are infected with the Hepatitis

C virus do not know they are infected because they do not look or feel sick.

What are the symptoms of chronic Hepatitis C?

Most people with chronic Hepatitis C do not have any symptoms. However,

if a person has been infected for many years, his or her liver may be damaged.

In many cases, there are no symptoms of the disease until liver problems

have developed. In persons without symptoms, Hepatitis C is often detected

during routine blood tests to measure liver function and liver enzyme (protein

produced by the liver) level.

How serious is chronic Hepatitis C?

Chronic Hepatitis C is a serious disease that can result in long-term

health problems, including liver damage, liver failure, liver cancer, or

even death. It is the leading cause of cirrhosis and liver cancer and the

most common reason for liver transplantation in the United States. Approximately

15,000 people die every year from Hepatitis C related liver disease.

What are the long-term effects of Hepatitis C?

Of every 100 people infected with the Hepatitis

C virus, about

- 75–85 people will develop chronic Hepatitis C virus infection; of

those,

- 60–70 people will go on to develop chronic liver disease

- 5–20 people will go on to develop cirrhosis over a period of

20–30 years

- 1–5 people will die from cirrhosis or liver cancer

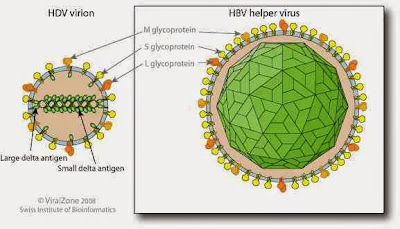

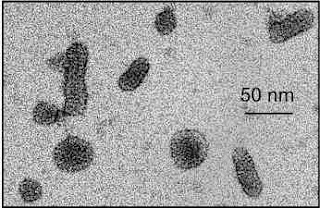

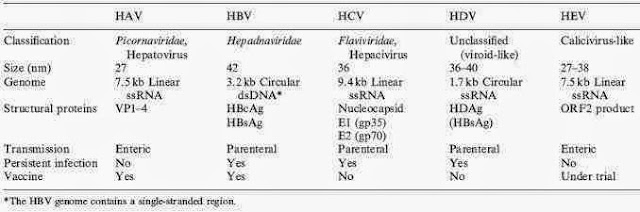

virus structure

Diagnosis

a number of diagnostic tests for hepatitis C, including HCV antibody enzyme immunoassay or ELISA, recombinant immunoblot assay, and quantitative HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR). HCV RNA

can be detected by PCR typically one to two weeks after infection,

while antibodies can take substantially longer to form and thus be

detected.

Chronic hepatitis C is defined as infection with the hepatitis C virus persisting for more than six months based on the presence of its RNA. Chronic infections are typically asymptomatic during the first few decades, and thus are most commonly discovered following the investigation of elevated liver enzyme levels

or during a routine screening of high-risk individuals. Testing is not

able to distinguish between acute and chronic infections. Diagnosis in the infant is difficult as maternal antibodies may persist for up to 18 months.

Hepatitis C testing typically begins with blood testing to detect the presence of antibodies to the HCV, using an enzyme immunoassay. If this test is positive, a confirmatory test is then performed to verify the immunoassay and to determine the viral load.

A recombinant immunoblot assay is used to verify the immunoassay and

the viral load is determined by a HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction.

If there are no RNA and the immunoblot is positive, it means that the

person tested had a previous infection but cleared it either with

treatment or spontaneously; if the immunoblot is negative, it means that

the immunoassay was wrong. It takes about 6–8 weeks following infection before the immunoassay will test positive. A number of tests are available as point of care testing which means that results are available within 30 minutes.

Liver enzymes are variable during the initial part of the infection and on average begin to rise at seven weeks after infection. The elevation of liver enzymes does not closely follow disease severity.

Liver biopsies are used to determine the degree of liver damage present; however, there are risks from the procedure. The typical changes seen are lymphocytes within the parenchyma, lymphoid follicles in portal triad, and changes to the bile ducts. There are a number of blood tests available that try to determine the degree of hepatic fibrosis and alleviate the need for biopsy.

It is believed that only 5–50% of those infected in the United States and Canada are aware of their status.

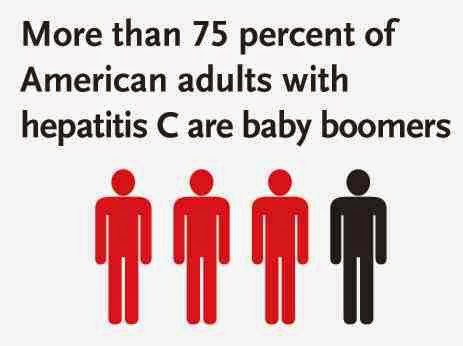

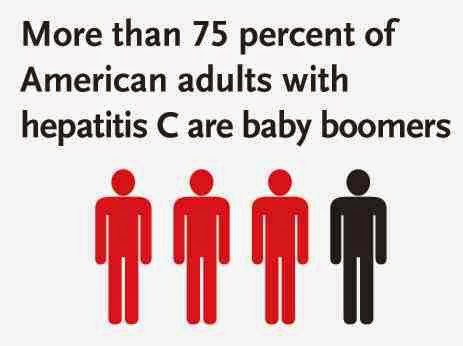

Testing is recommended in those at high risk, which includes injection

drug users, those who have received blood transfusions before 1992, those who have been in jail, those on long term hemodialysis, and those with tattoos. Screening is also recommended in those with elevated liver enzymes, as this is frequently the only sign of chronic hepatitis. Routine screening is not currently recommended in the United States. In 2012, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) added a recommendation for a single screening test for those born between 1945 and 1965.

Can a person have normal liver enzyme (e.g., ALT)

results and still have Hepatitis C?

Yes. It is common for persons with chronic Hepatitis C to have a liver

enzyme level that goes up and down, with periodic returns to normal or near

normal. Some infected persons have liver enzyme levels that are normal for

over a year even though they have chronic liver disease. If the liver enzyme

level is normal, persons should have their enzyme level re-checked several

times over a 6–12 month period. If the liver enzyme level remains normal,

the doctor may check it less frequently, such as once a year.

Who should get tested for Hepatitis C?

Talk to your doctor about being tested for Hepatitis

C if any of the following are true:

- You were born from 1945 through 1965

- You are a current or former injection drug user, even if you injected

only one time or many years ago.

- You were treated for a blood clotting problem before 1987.

- You received a blood transfusion or organ transplant before July

1992.

- You are on long-term hemodialysis treatment.

- You have abnormal liver tests or liver disease.

- You work in health care or public safety and were exposed to blood

through a needlestick or other sharp object injury.

- You are infected with HIV.

If you are pregnant, should you be tested for Hepatitis

C?

No, getting tested for Hepatitis C is not part of routine

prenatal care. However, if a pregnant woman has

risk factors for Hepatitis C

virus infection, she should speak with her doctor about getting tested.

What blood tests are used to test for Hepatitis

C?

Several different blood tests are used to test for Hepatitis C. A doctor

may order just one or a combination of these tests. Typically, a person

will first get a screening test that will show whether he or she has developed

antibodies to the Hepatitis C virus. (An antibody is a substance found in

the blood that the body produces in response to a virus.) Having a positive

antibody test means that a person was exposed to the virus at some time

in his or her life. If the antibody test is positive, a doctor will most

likely order a second test to confirm whether the virus is still present

in the person's bloodstream.

Treatment

HCV induces chronic infection in 50–80% of infected persons. Approximately 40–80% of these clear with treatment. In rare cases, infection can clear without treatment. Those with chronic hepatitis C are advised to avoid alcohol and medications toxic to the liver,and to be vaccinated for hepatitis A and hepatitis B. Ultrasound surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma is recommended in those with accompanying cirrhosis.

In general, treatment is recommended for those with proven HCV infection and signs of liver inflammation. As of 2010, treatments consist of a combination of pegylated interferon alpha and the antiviral drug ribavirin for a period of 24 or 48 weeks, depending on HCV genotype.This produces cure rates of between 70 and 80% for genotype 2 and 3, respectively, and 45 to 70% for other genotypes. When combined with ribavirin, pegylated interferon-alpha-2a may be superior to pegylated interferon-alpha-2b, though the evidence is not strong.

Combining either boceprevir or telaprevir with ribavirin and peginterferon alfa improves antiviral response for hepatitis C genotype 1. Adverse effects with treatment are common, with half of people getting flu like symptoms and a third experiencing emotional problems. Treatment during the first six months is more effective than once hepatitis C has become chronic.

If someone develops a new infection and it has not cleared after eight

to twelve weeks, 24 weeks of pegylated interferon is recommended. In people with thalassemia, ribavirin appears to be useful but increases the need for transfusions.

Sofosbuvir with ribavirin and interferon appears to be around 90% effective in those with genotype 1, 4, 5, or 6 disease.

Sofosbuvir with just ribavirin appears to be 70 to 95% effective in

type 2 and 3 disease but has a higher rate of adverse effects. Treatments that contain ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for genotype 1 has success rates of around 93 to 99% but is very expensive. In genotype 6 infection, pegylated interferon and ribavirin is effective in 60 to 90% of cases. There is some tentative data for simeprevir use in type 6 disease as well.

Vaccination

Is there a vaccine that can prevent Hepatitis C?

Not yet. Vaccines are available only for Hepatitis A and Hepatitis B.

Research into the development of a vaccine is under way.

Hepatitis C and Employment

Should a person infected with the Hepatitis C virus be restricted from working in certain jobs or settings?

CDC's recommendations

for prevention and control of the Hepatitis C virus infection state

that people should not be excluded from work, school, play, child care,

or other settings because they have Hepatitis C. There is no evidence

that people can get Hepatitis C from food handlers, teachers, or other

service providers without blood-to-blood contact.

Prevention

As of 2011, no vaccine protects against contracting hepatitis C. However, there are a number under development and some have shown encouraging results. A combination of harm reduction strategies, such as the provision of new needles and syringes and treatment of substance use, decreases the risk of hepatitis C in intravenous drug users by about 75%.The screening of blood donors is important at a national level, as is adhering to universal precautions within healthcare facilities. In countries where there is an insufficient supply of sterile syringes, medications should be given orally rather than via injection (when possible).

Hepatitis C Diet

Such a diet contains nutrient-rich foods that support the

liver as well as overall health.

Food recommendations:

- cold water fish high in omega

3’s

- leafy green vegetables

- root vegetables such as beets

and carrots

- artichoke hearts

- grass-fed meats

- fruits and vegetables high in

antioxidants

People should especially avoid:

- processed foods

- vegetables oils

- trans fats

- fast food or junk food

- sugar

- alcohol

Vitamins for Hepatitis C

The best source of vitamins and minerals is found in a

nutrient-rich diet. Sometimes, getting ideal amounts of certain nutrients in

the diet can be difficult due to nutrient-deficient soils or improper

metabolism in the body.

The following is an overview of vitamins for hep C. A person

may need more or less of these depending on their diet, digestion and personal

circumstances.

- Vitamin B complex

- Vitamin C

- Vitamin D3

- Magnesium

- Selenium

- Essential Fatty Acids, Omega

3’s

- Probiotics

Hepatitis C Diet

Such a diet contains nutrient-rich foods that support the liver as well as overall health.

Food recommendations:

- cold water fish high in omega 3’s

- leafy green vegetables

- root vegetables such as beets and carrots

- artichoke hearts

- grass-fed meats

- fruits and vegetables high in antioxidants

People should especially avoid:

- processed foods

- vegetables oils

- trans fats

- fast food or junk food

- sugar

- alcohol

Vitamins for Hepatitis C

The

best source of vitamins and minerals is found in a nutrient-rich diet.

Sometimes, getting ideal amounts of certain nutrients in the diet can be

difficult due to nutrient-deficient soils or improper metabolism in the

body.

The following is an overview of vitamins for hep C. A

person may need more or less of these depending on their diet, digestion

and personal circumstances.

- Vitamin B complex

- Vitamin C

- Vitamin D3

- Magnesium

- Selenium

- Essential Fatty Acids, Omega 3’s

- Probiotics

- See more at: http://www.herbalremediesadvice.org/hepatitis-c.html#sthash.vwh03V0B.dpuf

Hepatitis C Diet

Such a diet contains nutrient-rich foods that support the liver as well as overall health.

Food recommendations:

- cold water fish high in omega 3’s

- leafy green vegetables

- root vegetables such as beets and carrots

- artichoke hearts

- grass-fed meats

- fruits and vegetables high in antioxidants

People should especially avoid:

- processed foods

- vegetables oils

- trans fats

- fast food or junk food

- sugar

- alcohol

Vitamins for Hepatitis C

The

best source of vitamins and minerals is found in a nutrient-rich diet.

Sometimes, getting ideal amounts of certain nutrients in the diet can be

difficult due to nutrient-deficient soils or improper metabolism in the

body.

The following is an overview of vitamins for hep C. A

person may need more or less of these depending on their diet, digestion

and personal circumstances.

- Vitamin B complex

- Vitamin C

- Vitamin D3

- Magnesium

- Selenium

- Essential Fatty Acids, Omega 3’s

- Probiotics

- See more at: http://www.herbalremediesadvice.org/hepatitis-c.html#sthash.vwh03V0B.dpuf

Hepatitis C Diet

Such a diet contains nutrient-rich foods that support the liver as well as overall health.

Food recommendations:

- cold water fish high in omega 3’s

- leafy green vegetables

- root vegetables such as beets and carrots

- artichoke hearts

- grass-fed meats

- fruits and vegetables high in antioxidants

People should especially avoid:

- processed foods

- vegetables oils

- trans fats

- fast food or junk food

- sugar

- alcohol

Vitamins for Hepatitis C

The

best source of vitamins and minerals is found in a nutrient-rich diet.

Sometimes, getting ideal amounts of certain nutrients in the diet can be

difficult due to nutrient-deficient soils or improper metabolism in the

body.

The following is an overview of vitamins for hep C. A

person may need more or less of these depending on their diet, digestion

and personal circumstances.

- Vitamin B complex

- Vitamin C

- Vitamin D3

- Magnesium

- Selenium

- Essential Fatty Acids, Omega 3’s

- Probiotics

- See more at: http://www.herbalremediesadvice.org/hepatitis-c.html#sthash.vwh03V0B.dpuf

Hepatitis C Diet

Such a diet contains nutrient-rich foods that support the liver as well as overall health.

Food recommendations:

- cold water fish high in omega 3’s

- leafy green vegetables

- root vegetables such as beets and carrots

- artichoke hearts

- grass-fed meats

- fruits and vegetables high in antioxidants

People should especially avoid:

- processed foods

- vegetables oils

- trans fats

- fast food or junk food

- sugar

- alcohol

Vitamins for Hepatitis C

The

best source of vitamins and minerals is found in a nutrient-rich diet.

Sometimes, getting ideal amounts of certain nutrients in the diet can be

difficult due to nutrient-deficient soils or improper metabolism in the

body.

The following is an overview of vitamins for hep C. A

person may need more or less of these depending on their diet, digestion

and personal circumstances.

- Vitamin B complex

- Vitamin C

- Vitamin D3

- Magnesium

- Selenium

- Essential Fatty Acids, Omega 3’s

- Probiotics

- See more at: http://www.herbalremediesadvice.org/hepatitis-c.html#sthash.vwh03V0B.dpuf

References

- Mast EE (2004). "Mother-to-infant hepatitis C virus transmission and breastfeeding". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 554: 211–6. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-4242-8_18. PMID 15384578.

- Shivkumar,

S; Peeling, R; Jafari, Y; Joseph, L; Pant Pai, N (2012-10-16).

"Accuracy of Rapid and Point-of-Care Screening Tests for Hepatitis C: A

Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.". Annals of Internal Medicine 157 (8): 558–66. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-8-201210160-00006. PMID 23070489.

- Moyer,

VA; on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force*

(2013-06-25). "Screening for Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Adults: U.S.

Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement.". Annals of Internal Medicine 159 (5): 349–57. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-5-201309030-00672. PMID 23798026.

- Moyer,

VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force (2013-09-03). "Screening for

hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task

Force recommendation statement.". Annals of internal medicine 159 (5): 349–57. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-5-201309030-00672. PMID 23798026.

- Senadhi, V (July 2011). "A paradigm shift in the outpatient approach to liver function tests". Southern Medical Journal 104 (7): 521–5. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31821e8ff5. PMID 21886053.

- Smith

BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al. (August 2012). "Recommendations for

the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons

born during 1945–1965". MMWR Recomm Rep 61 (RR-4): 1–32. PMID 22895429.

- Halliday, J; Klenerman P; Barnes E (May 2011). "Vaccination for hepatitis C virus: closing in on an evasive target" (PDF). Expert review of vaccines 10 (5): 659–72. doi:10.1586/erv.11.55. PMC 3112461. PMID 21604986.

- Hagan, H; Pouget, ER, Des Jarlais, DC (2011-07-01). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to prevent hepatitis C virus infection in people who inject drugs". The Journal of infectious diseases 204 (1): 74–83. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir196. PMC 3105033. PMID 21628661.

- Torresi, J; Johnson D; Wedemeyer H (June 2011). "Progress in the development of preventive and therapeutic vaccines for hepatitis C virus". Journal of hepatology 54 (6): 1273–85. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2010.09.040. PMID 21236312.

- Ilyas, JA; Vierling, JM (August 2011). "An overview of emerging therapies for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C". Clinics in liver disease 15 (3): 515–36. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2011.05.002. PMID 21867934.

- Liang, TJ; Ghany, MG (May 16, 2013). "Current and future therapies for hepatitis C virus infection.". The New England Journal of Medicine 368 (20): 1907–17. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1213651. PMID 23675659.

- Awad

T, Thorlund K, Hauser G, Stimac D, Mabrouk M, Gluud C (April 2010).

"Peginterferon alpha-2a is associated with higher sustained virological

response than peginterferon alfa-2b in chronic hepatitis C: systematic

review of randomized trials". Hepatology 51 (4): 1176–84. doi:10.1002/hep.23504. PMID 20187106.

- Foote

BS, Spooner LM, Belliveau PP (September 2011). "Boceprevir: a protease

inhibitor for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C". Annals of Pharmacotherapy 45 (9): 1085–93. doi:10.1345/aph.1P744. PMID 21828346.

- Smith

LS, Nelson M, Naik S, Woten J (May 2011). "Telaprevir: an NS3/4A

protease inhibitor for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C". Annals of Pharmacotherapy 45 (5): 639–48. doi:10.1345/aph.1P430. PMID 21558488.

- Ghany MG, Nelson DR, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB (October 2011). "An

update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection:

2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of

Liver Diseases". Hepatology 54 (4): 1433–44. doi:10.1002/hep.24641. PMC 3229841. PMID 21898493.

- Alavian

SM, Tabatabaei SV (April 2010). "Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in

polytransfused thalassaemic patients: a meta-analysis". J. Viral Hepat. 17 (4): 236–44. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01170.x. PMID 19638104.

- De Clercq, E (Nov 15, 2013). "Dancing with chemical formulae of antivirals: A panoramic view (Part 2).". Biochemical pharmacology 86 (10): 1397–410. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.09.010. PMID 24070654.

- Hoofnagle, JH; Sherker, AH (Apr 17, 2014). "Therapy for hepatitis C--the costs of success.". The New England Journal of Medicine 370 (16): 1552–3. doi:10.1056/nejme1401508. PMID 24725236.

- Bunchorntavakul,

C; Chavalitdhamrong, D; Tanwandee, T (Sep 27, 2013). "Hepatitis C

genotype 6: A concise review and response-guided therapy proposal.". World journal of hepatology 5 (9): 496–504. doi:10.4254/wjh.v5.i9.496. PMID 24073301.

- Sanders, Mick (2011). Mosby's Paramedic Textbook. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 839. ISBN 9780323072755.

- Ciria R, Pleguezuelo M, Khorsandi SE, et al. (May 2013). "Strategies to reduce hepatitis C virus recurrence after liver transplantation". World J Hepatol 5 (5): 237–50. doi:10.4254/wjh.v5.i5.237. PMC 3664282. PMID 23717735.

- Coilly

A, Roche B, Samuel D (February 2013). "Current management and

perspectives for HCV recurrence after liver transplantation". Liver Int. 33 Suppl 1: 56–62. doi:10.1111/liv.12062. PMID 23286847.

- Hepatitis C and CAM: What the Science Says. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). March 2011. (Retrieved 7 March 2011)

- Liu,

J; Manheimer E; Tsutani K; Gluud C (March 2003). "Medicinal herbs for

hepatitis C virus infection: a Cochrane hepatobiliary systematic review

of randomized trials". The American journal of gastroenterology 98 (3): 538–44. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07298.x. PMID 12650784.

- Rambaldi, A; Jacobs, BP; Gluud, C; (Hepato-Biliary Group) (2007-10-17). "Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003620 (2nd rev.). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003620.pub2. PMID 17943794.

- Fung J, Lai CL, Hung I et al. (September 2008). "Chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 6 infection: response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin". The Journal of Infectious Diseases 198 (6): 808–12. doi:10.1086/591252. PMID 18657036.

- Morgan

RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y (March 2013).

"Eradication of Hepatitis C Virus Infection and the Development of

Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Meta-analysis of Observational Studies". Annals of Internal Medicine 158 (5 Pt 1): 329–37. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00005. PMID 23460056.

- Lozano,

R (2012-12-15). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death

for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the

Global Burden of Disease Study 2010.". Lancet 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

- Yu ML; Chuang WL (March 2009). "Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Asia: when East meets West". J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 24 (3): 336–45. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05789.x. PMID 19335784.

- Published data for 1982–2010. "Viral Hepatitis Statistics & Surveillance". Viral Hepatitis on the CDC web site. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Table 4.5. "Number

and rate of deaths with hepatitis C listed as a cause of death, by

demographic characteristic and year — United States, 2004–2008". Viral Hepatitis on the CDC web site. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

_-_en.svg.png)